John Berger doesn’t need me to defend him. A Booker Prize winning novelist, poet, essayist and broadcaster, he was amongst Britain’s most admired public intellectuals. His famous and groundbreaking TV series (and subsequent best selling book) Ways of Seeing, although not particularly representative of his work, has been massively influential, transforming our understanding of the cultural significance of pictures.

From the very first scene, in which Berger takes a knife to a Botticelli, it was clear that ‘Ways of Seeing’ was an assault on thoughtless reverence […] One of the reasons the series is so lastingly influential is that Berger empowers the viewer, transforming them from passive consumer of high culture to detective …

— Olivia Laing in The Guardian

Berger was a committed Marxist (although never a card-carrying Communist) and this is often enough to cause some readers to dismiss his ideas.

I recently read a very popular Substack post by Alice Gribbin, entitled Do You Want To See? Yes, I thought. I do. At the time of writing, it has been liked 160 times, re-stacked 45 times and has 16 comments. The vast majority of the comments are brimming with praise for Alice’s spirited, uncompromising text. As the title suggests, her argument is concerned with the experience of looking. She begins by questioning the role of theory, wondering if there is any “substance” to be found there. The implication, of course, is that theory, discourse of any sort, is arid, empty and lifeless. Like looking for a piece of fruit in a motorway service station, apparently. Alice writes engagingly, with several elegant turns of phrase.

This is fresh and interesting, I thought.

Then, unsurprisingly, Alice turns her attention to the 1970s. I think it’s worth quoting this particular passage at length:

In the bleak mid-January of 1972, British households with their television tuned to BBC Two were invited by the critic John Berger to join him in “question[ing] the assumptions” of the Western art tradition. Berger’s audience was the general public, and the analysis he offered not only was taken up, quite immediately, as the dominant intellectual approach to the nude but remained so in the decades that followed.

‘Ways of Seeing’ defined the nude as a naked person made into an object and thereby stripped of their humanity. For Berger and generations of feminist critics and artists, the nude in Western art history is exclusively female, is passive, and so embodies stereotypes of femininity that both reflect and reinforce the status of women (as object, as vulnerable, as sexually available) in Western societies. That Berger was oblivious to the ancient tradition of the nude form is plain. Moreover, he psychologized the nude figure—saying “the truth about oneself” is denied her—to the point of wild conspiracy.

We were raised in a culture where the conspiracy theory of the male gaze received near total institutional endorsement. Nakedness in art existed, according to our educations, for the purpose of “male consumption.” Art was said to be a service industry like any other, with male artists serving their male patrons’ libidinous needs.

Feminist scholarship emerged as a political project and an expression of the concerns, often intensely personal, of a class of professional women living in the seventies. Art was a wall they could tack their social hang-ups onto. Half a century has now passed. Their hang-ups are not ours.

Blimey. Who are “we”? What is “theirs” and “ours”? I began to feel a little alienated. Am I one of us?

Alice mentions Berger by name, but also generations of feminist scholars, critics or artists, whose “hang-ups” she peremptorily dismisses. Later on, she name-checks Kristeva, Kant, and Derrida. Quite the roll call! She considers the male gaze to be a “conspiracy theory” and claims that Berger was “oblivious” to ancient art! 1

Kris, and others, loved it:

This was a riotous evisceration of everything wrong with the way we’ve been trained to talk about art. The merciless takedown of Berger and his descendants, the gleeful disregard for academic handwringing, the refusal to pretend art exists for some committee-approved discourse-industrial complex: chef’s kiss.

Also, the sheer nerve of dismissing half a century of feminist critique with “their hang-ups are not ours” is so audacious I almost stood up and clapped.

Sheer nerve indeed. This all reminded me of the ‘Academy of the Overrated’ scene in Manhattan:

I’ve encountered a few examples of this kind of thing on Substack and elsewhere. I suppose cancelling John Berger et al could be a plucky move for an aspiring arts journalist. A self-styled “aesthete”, Alice refers to herself as a poet (like Berger) who is “remystifying art” (most unlike Berger).2 Her writing is full of rhetorical flourishes, as befits a contributor to the New York Review of Books. It sounds smart and savvy.

I was drawn to one of her recent posts entitled How do the animals treat you? A line from a poem. It reminded me of one of my favourite Berger essays, Why Look at Animals?

The 19th century, in western Europe and North America, saw the beginning of a process, today being completed by 20th century corporate capitalism, by which every tradition which has previously mediated between man and nature was broken.

— John Berger, ‘Why Look at Animals?’, 1977

This is classic Berger. It’s not dissimilar in style to Gribbin; broad in scope, direct, precise and critical. The intention, though, is radically different. Berger is a storyteller, first and foremost, and the purpose of the essay is to educate readers about the impact of industrialisation on our relationship with animals. Berger does not hide his politics or ideological standpoint. It is clear from the outset that the cause of the breakdown in our relationship with nature was, what he referred to elsewhere as, “fascist capital”.3 On the subject of his Marxist views, Berger was never shy or embarrassed. On the contrary, he was proud to claim Marx as a great thinker and still relevant to contemporary life.4

Berger wanted us to look hard at the world, including images made about it. He wanted us to see pictures as part of our everyday reality, not reified in private collections, country houses and museums, for the delectation of an elite, but available to us all. He wished to democratise art so that we all had a stake in it. He was opposed to obfuscation, received wisdom, ‘common sense’, The Western Canon, league tables of ‘great’ artists, the status quo. What he offered were the lessons of history, knowledge and clear-eyed analysis.

Inspired by Walter Benjamin, he was interested in the mechanical reproduction of images and the consequent loss of art’s ‘aura’.5 He understood that images shape our sense of what’s real. They are coercive, persuasive, phantasmagoric. Photographs, in particular, are intensely seductive. They pretend to show us pictures of things as they are when, in fact, they are highly constructed abstractions.6 Berger’s writing attempts to expose the values embedded in works of art so that we can see them with fresh eyes and understand the cultural work that they continue to do across time.

His writing is full of remarkable insights, original thinking and illuminating argument which helps transform the way we see things. It is, to contradict Gribbin, full of substance.

Peter Fraser’s lovely photograph above was made about seven years after Why Look at Animals? was published. Early in the essay, Berger reminds us that:

Animals first entered the imagination as messengers and promises. For example, the domestication of cattle did not begin as a simple prospect of milk and meat. Cattle had magical functions, sometimes oracular, sometimes sacrificial […] Animals are born, are sentient and are mortal. In these things they resemble man. In their superficial anatomy -less in their deep anatomy - in their habits, in their time, in their physical capacities, they differ from man. They are both like and unlike.7

Fraser’s image appears, on first viewing, to be relatively mundane - a landscape view of a farmer’s field, containing cows and chickens, seen through a hedge. The picture appears in a sequence entitled 12 Day Journey. One assumes that the picture was made on a walk through the countryside during a kind of secular pilgrimage. On closer inspection, we notice that one of the cows has looked up from its grazing to return the gaze of the photographer. Back to Berger:

In the first stages of the industrial revolution, animals were used as machines. As also were children.

Devastating stuff. The kind of razor-sharp prose that makes you question your understanding of basic facts. Berger quickly turns his attention to the ways in which animals and humans exchange looks.

The eyes of an animal when they consider a man are attentive and wary. The same animal may well look at other species in the same way. He does not reserve a special look for man. But by no other species except man will the animal's look be recognised as familiar. Other animals are held by the look. Man becomes aware of himself returning the look. The animal scrutinises him across a narrow abyss of noncomprehension. This is why the man can surprise the animal. Yet the animal - even if domesticated - can also surprise the man. The man too is looking across a similar, but not identical, abyss of non-comprehension. And this is so wherever he looks. He is always looking across ignorance and fear. And so, when he is being seen by the animal, he is being seen as his surroundings are seen by him. His recognition of this is what makes the look of the animal familiar. And yet the animal is distinct, and can never be confused with man. Thus, a power is ascribed to the animal, comparable with human power but never coinciding with it. The animal has secrets which, unlike the secrets of caves, mountains, seas, are specifically addressed to man.

Without substance? I beg to differ.

Try reading this carefully, taking it in and reflecting on the beautiful, subtle and lucid argument. Now look again at Peter Fraser’s photograph, the cow looking back at the photographer and, by implication, us, and tell me that your understanding of this image has not been altered irrevocably.

Here’s another poignant photograph, one of my personal favourites, of the “abyss of noncomprehension” shared by humans and animals:

Returning briefly to Alice Gribbin’s post about the nude, her rallying cry appears to be the need for fewer questions and more looking, a desire for transcendence uncomplicated by theory:

We’re here and here to look.

Again, the royal ‘we’. Perhaps its understandable that some young (younger than me anyway) writers want to kick over the statues, rejecting the ideas of previous generations. I’m no fan of International Art English and I have seen exhibitions that were spoiled by excessive curatorial verbiage. I understand why some people are frustrated by aspects of contemporary cultural politics. Power is not evenly distributed. It’s the urge to go backwards, to some mythical prelapsarian golden age, that I find troubling.

Is it possible to look without thinking, without asking questions and having questions asked of you? Aren’t the eyes and the brain connected? Should we not be grateful for the insights of radical thinkers, those who have dared to question institutional power and vested interests? Even if we don’t agree with their conclusions, do they not deserve our intelligent engagement? Brushing off the concerns of decades of feminist activists as mere “social hangups” strikes me as click bait.

What concerns me about posts like this (it’s not an isolated example by any means) is the notion that there is such a thing as ‘Great Art’, that ‘we’ all share similar views about what constitutes its greatness, and that everything before the late 1960s was the high water mark of cultural achievement. Some writers go even further, claiming that in those hallowed years before ‘postmodernism’, ‘we’ all experienced freedom of speech and were not oppressed by ‘political correctness’, ‘identity politics’ and ‘Bad Ideas’. Its the cultural commentator equivalent of Reform (formerly UKIP) politics. Or an episode of The Good Old Days.

I thought long and hard about whether or not to publish this post. Is it worth it? Why bother? What will it resolve? I sought wise counsel. As you can see, I decided to go ahead. It’s a fair reflection of what I think and how I see things. I’m willing to admit that I may have got it all wrong. My concerns may be groundless.

I don’t wish Alice any ill will. I’m sure her writing career will continue to flourish. I’m sure she doesn’t give a hoot about why I think, but might she be wise to select her targets more judiciously in future?

Anyone concerned with the business of looking could find no better guide than John Berger.8

There is so much of Berger’s work that I admire that it would be impossible to do it justice here. My favourite book is A Fortunate Man. I love all of his collaborations with the photographer Jean Mohr. His essay The Suit and the Photograph, about a picture by August Sander, is wonderful. Of all the clips available online, I particularly like this brief BBC interview, in which his humanity, sensitivity, humour and compassion really shine through:

Here’s Geoff Dyer on his late friend’s achievements and lasting legacy:

No one has ever matched Berger’s ability to help us look at paintings or photographs “more seeingly”, as Rilke put it in a letter about Cézanne […] Berger brought immense erudition to his writing but, as with D. H. Lawrence, everything had to be verified by appeal to his senses […] All that interested him about his own life, he once wrote, were the things he had in common with other people […] The film Walk Me Home which he co- wrote and acted in was, in his opinion, “a balls-up” but in it Berger utters a line that I think of constantly – and quote from memory – now: “When I die I want to be buried in land that no one owns.” In land, that is, that belongs to us all.

These posts will always be free but, if you enjoy reading them, you can support my analogue photography habit by contributing to the film fund. All donations of whatever size are very gratefully received.

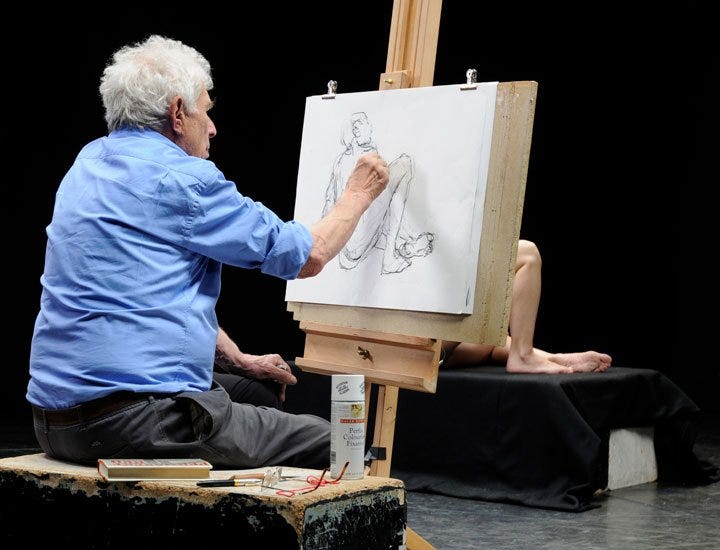

I suspect that John Berger has looked at more ancient statues than Gribbin has had hot dinners. He certainly looked at his share of living nude bodies: https://www.artangel.org.uk/project/life-class/

I’m not really sure what this “remystifying art” means since Gribbin’s essay seems critical of art theorists who have made art mysterious through opaque and academic discourse. Perhaps I have misunderstood. Is art too obvious and easily understood? Does art need to be (re)mystified?

Given that Gribbin describes me as a “Marxist” (imagining, I suppose, that I might be embarrassed by the label) I’m guessing Karl Marx might be counted, along with Berger et al in her Academy of the Overrated.

Reality, after all, isn’t flat and doesn’t have four edges. A camera lens is circular. Photographs are (mostly) rectilinear. Most people are binocular. Cameras are monocular.

The use of the male pronoun is a little jarring, admittedly, but not uncommon for 1977.

Only if you actually read him, that is.

It’s only a point of view about a point of view.

Reading and listening to Berger gave me new eyes regardless of whether I can see what he sees.

Thanks Jon. Gribbin’s ‘we, we, we’ assertions really did get my goat. You should have seen the look it gave me.