This post, along with a few that follow intermittently, will be about strategies to support young photographers (A-level students in my case) to develop their own ideas and a more personal relationship with photography.

Developing ideas for personal projects can sometimes be a tricky process. My hunch is that an interesting investigation can often begin with a good question. But how do young photographers do this?

As an A-level photography teacher, my main job is to support students, often beginner photographers, in identifying something that interests them but that isn’t too easy or immediate. Many students, like most other “amateurs of the lens”, are drawn to pictures of graffiti or snapshots of their friends. They are overly influenced by the pictures they have already seen in abundance on social media or in adverts. They may not have seen many unconventional photographs and some of them don’t like to venture much beyond their local environment (physically and psychologically). Their tacit understanding of photography can be unhelpful and constraining.

So what can teachers do to help?

In recent years, I have tried a variety of prompts and exercises, some of which I plan to share here, that are designed to inform and challenge - to open up new ways of thinking, being and doing1. I used the following example recently, an idea I ‘borrowed’ from a brilliant course at The Photographers’ Gallery a few years ago. I hope you find it helpful too.

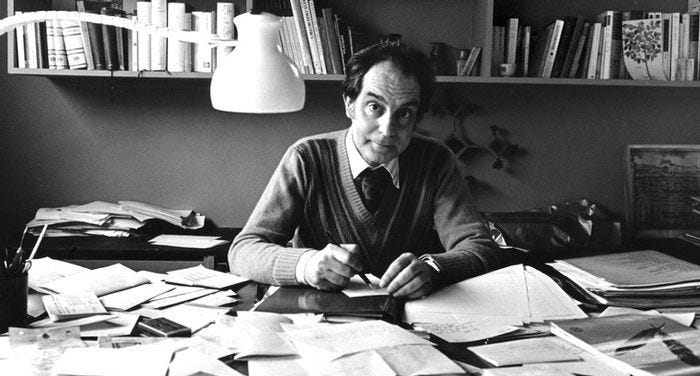

Italo Calvino wrote his story 'The Adventure of a Photographer’ in the 1950s and it was published, along with other adventures, in the 1970s under the title Difficult Loves.

I gave the students a printed copy of the story and asked them to read it for homework. Their task was to make a list of all the different methods used (or suggested) by the central character for making photographs. I warned them that the story was quite tricky to read (and contained outdated, sexist attitudes) but I wanted them to stick with difficulty and practice their persistence.

Antonino, the 'hero' of Calvino’s story, is initially reluctant to pick up a camera. He is unmarried, an executive in a production firm and an amateur "philosopher" of current events. Slowly, he becomes intrigued by his married friends and their "bulging game bags" of snapshots and decides to "join the ranks of the amateurs of the lens."

He is not dissimilar to beginner photographers. He is drawn into photography slowly, cautiously. He is ambivalent about its merits. He quickly notices that some of his friends boast of their technical skill, whereas others claim to be making "art". However, he feels, the "secret" of photography "lies elsewhere”.

He begins his "adventure" fairly innocently, being asked to take snapshots of people on weekend outings. However, he soon realises that photography is a complex process.

The line between the reality that is photographed because it seems beautiful to us and the reality that seems beautiful because it has been photographed is very narrow.

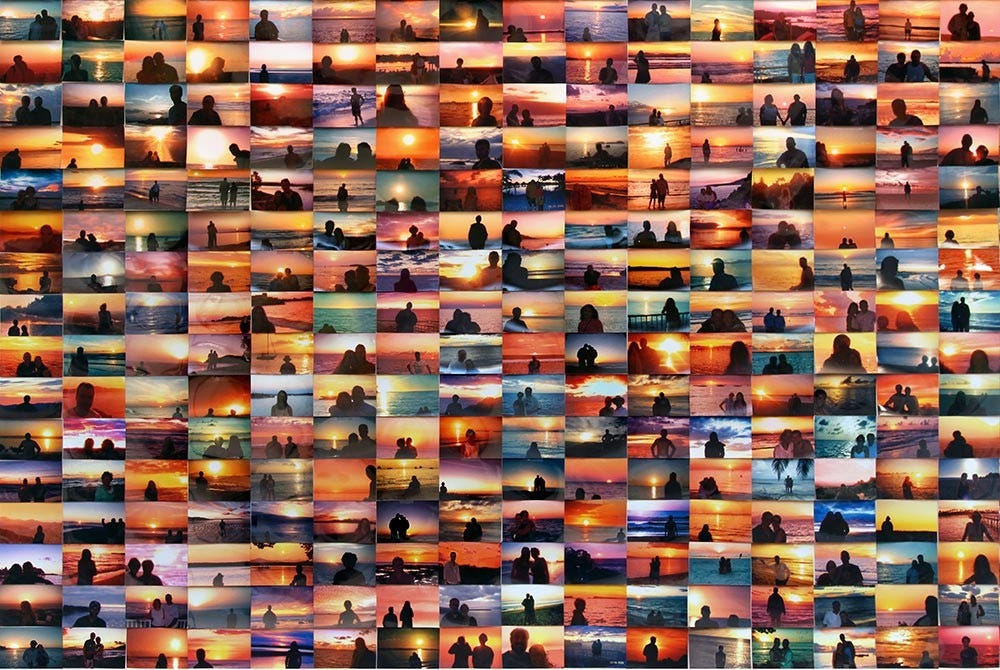

My class had a very interesting discussion about this. I asked the group to think of a subject that they considered beautiful, that might compel them to take/make a photograph. A sunset at the beach was the unanimous suggestion.

I then asked them to think of a subject that might be considered aesthetically unappealing but that could be transformed through photography. We discussed messy bedrooms, smashed ice cream cones and dirt.

We then reviewed their lists of strategies, culled from the story. How does Antonino get to grips with photography? He suggests (and sometimes carries out) a series of experiments, each one exploring an attitude towards the medium. Here are the examples we found together:

snap at least one picture a minute, from the instant you open your eyes in the morning to when you go to sleep

taking "spontaneous" snapshots of people having fun at the beach

attempting to capture movement of a ball game by using unusual angles

taking posed portraits in a studio with a "box camera" on a tripod and studio lights

using costumes and props to create an "ideal postcard" style image

using dramatic poses to create the illusion of action

"did he want to photograph dreams?"

taking 19th century style formal portraits of a woman in evening dress

photographing the nude body

experimenting with the "latest equipment" e.g. telescopic lenses

taking pictures of a sleeping subject (with a flash)

using a "hidden" lens to create candid street photographs, the subject unaware of the photographer's "gaze"

keeping a photographic diary of domestic snapshots

keeping a "catalogue" of mundane photographs of "everything in the world that resists photography" e.g. the empty corner of a room

photographing domestic objects (still life)

envying the news and fashion photographers who capture "exceptional moments"

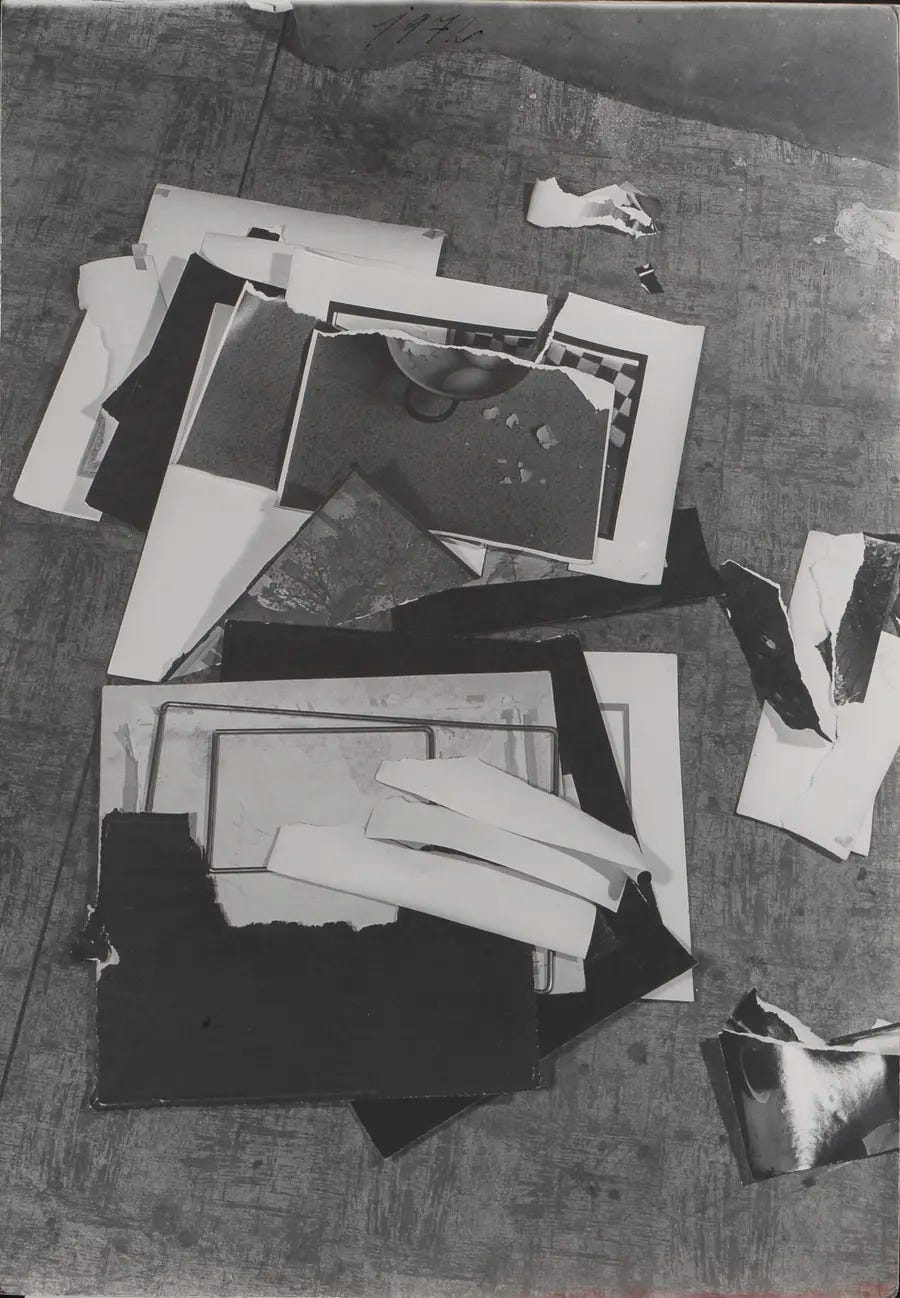

tearing up photographs, creating "a pile of fragments of private images, against the creased background of massacres and coronations"

creating diptychs of two different photographs that, by chance, appear to fit together

This is a pretty comprehensive list of ways to make photographs, a full-ish range of genres and approaches, just one of which could be the basis of an entire Personal Investigation.

In the end, Antonino realises that he has exhausted all the ways he can think of to make photographs.

To get all this into one photograph he had to acquire an extraordinary technical skill, but only then would Antonino quit taking pictures. Having exhausted every possibility, at the moment when he was coming full circle, Antonino realised that photographing photographs2 was the only course that he had left—or, rather, the true course he had obscurely been seeking all this time.

Having experimented with various types of “straight” photography, Antonino anticipates the experiments of various art photographers and conceptual artists.

Antonino oscillates between two types of photographic practice which we could call objective and subjective. This, of course, relates to John Szarkowski's categories of windows (looking outward at the world) and mirrors (looking inward at the imagination). More on Mirrors and Windows in a future post3.

Antonino realises very quickly that what lurks in his “black instrument” is nothing but a kind of madness. This madness is a forking path. One path beckons outward, toward the doomed and impossible desire to document everything that exists and happens before it is lost forever. The camera must record all reality, all history; only then would it begin making some sort of crazy sense. The other one leads inexorably within, into the labyrinths from which the eyes, windows of the soul, look at the world outside.

Antonino’s adventure is fuelled by his many questions about photography. What happens if I take a picture like this? How does this type of camera or lens change the way things look? How can photography help me understand what I can see and feel? How does taking/making photographs affect my relationship to the world? He has the inquisitiveness of an amateur, a novice, a beginner. Along with persistence, this seems like the most useful habit of mind for teachers to cultivate in their students.

My final request of the class was to reflect on their own interests - the things they cared about or were bothered by - and to devise a question that could form the basis of their own adventure in photography - their Personal Investigations.

I’m looking forward to seeing what they come up with over the next couple of weeks.

Do let me know in the comments if any of this strikes a chord with you. If you don’t know the story (and Calvino’s work more generally) I can heartily recommend it.

My next post will be about photographs as mirrors and/or windows and the “forking path” that leads either outward or within (or maybe a bit of both).

Our Threshold Concepts for Photography offer lots of ideas for ways to think about photography.

Thanks to the marvellous Anna Lucas for introducing me to the work of Jiro Takamatsu, whose photographs of photographs are a constant source of ideas and inspiration.

Update:

Mirrors & Windows

This post, part of an intermittent series, is about strategies to support young photographers (A-level students in my case) to develop a personal and critical relationship with photography. It’s aimed at photography educators, those who have subscribed previously to the

Hi Jon, I teach A Level Photography in Leeds at a large sixth form. We have about 80 students on the course and the idea of supporting students to develop their own ideas and independence is something that is always a challenge. I'm currently doing an action research project on developing students creativity and independence inspired by Mary Corita's art department rules. I found this a really interesting read, and it is good to know other teachers face similar challenges. Thank you for sharing!

Very much enjoying your insights. I've picked up a copy of the book and shall challenge myself to respond as if a student of yours.