We’re all taught from a very early age that copying is bad. I once got caught copying from notes I’d scrawled up my arm in a French test at school. Oh, the shame!

According to Oscar Wilde, “Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery that mediocrity can pay to greatness.” Hmmm. Who wants to be mediocre? However, I’d like to present a case in defence of copying, and its bedfellows imitation, borrowing, influence etc., plus the urge to pay homage to someone you admire.1

We have an uneasy relationship with copying in the arts, but the idea of originality is largely a 20th century (modernist) obsession. Before the middle of the 19th century, artists were trained to copy, literally, and their ability to make visual imitations from accepted models of excellence was a significant feature of their training. The late 19th and 20th centuries ushered in a modern cult of progress and ideas about the avant-garde. Artists were meant to innovate and experiment on behalf of the rest of society, leading from the front.2 In the later 20th century, artists began to question this idea. The past became a resource to plunder, a postmodern pick 'n' mix of cultural goodies to be appropriated and transformed. John Baldessari, amongst others, has had lots of fun with this.

It’s true that there is a strong classicist dimension to modernist art. T. S Eliot’s essay Tradition and the Individual Talent is concerned with the dynamic and progressive relationship between contemporary poetry and the literature of the past.

The most individual parts of his [the poet's] work may be those in which the dead poets, his ancestors, assert their immortality most vigorously.

— T. S. Eliot

But Eliot isn’t celebrating straightforward imitation. Poetry and photography are connected in interesting ways but their relationship to copying and influence is quite different. For example, the issue of appropriation in photography is still hot news, it seems, and this is only exacerbated by concerns about post-production software and AI. Chat GPT poems are pretty terrible but AI images, masquerading as photographs, win prizes.

Of all the arts, photography perhaps has the most troubled relationship with ideas of copying or imitation. Its 'invention'3 was linked to a desire for better, more accurate copies of things - landscapes, objects and faces - so that scientists, the authorities and artists could have more reliable documents. Photographers struggled to establish their discipline as a branch of the 'fine' arts, to disassociate it from mechanical reproduction. But let’s not get distracted by tired debates about whether, or not, photographers are artists.

I like to look at pictures, all kinds. And all those things you absorb come out subconsciously one way or another [...] this kind of subconscious influence is good, and it certainly can work for one. In fact, the more pictures you see, the better you are as a photographer.

— Robert Mapplethorpe

This statement is pretty contentious. I’ve heard some photographers say that they deliberately avoid looking at others’ work for fear of being overly seduced by alternative ways of seeing, by the temptation to copy. Copying, for them, connotes dilution or inauthenticity. No-one wants to be a pale imitation of something more impressive. But pretending that you aren’t influenced by other image makers is disingenuous. We all absorb the influence of others, so why not embrace it?

Rather than deny influence, some photographers have created deliberate homages to other artists they admire. This can include a quite literal type of copying but, invariably, something more subtle and sophisticated is at work.4

My last post was about exhibiting my pictures of a trip to Rome. Having seen the magnificent Guido Guidi show at Maxxi, I found myself influenced by aspects of his work. I was so excited about seeing his pictures that I couldn’t help but absorb some of his compositional and aesthetic concerns. I’m not at all bothered by this. In fact, I’m rather pleased that I had the opportunity to respond so directly to one of my photography heroes. Was this an example of copying, imitation, influence, appropriation, re-imagining or homage? Probably all of the above.

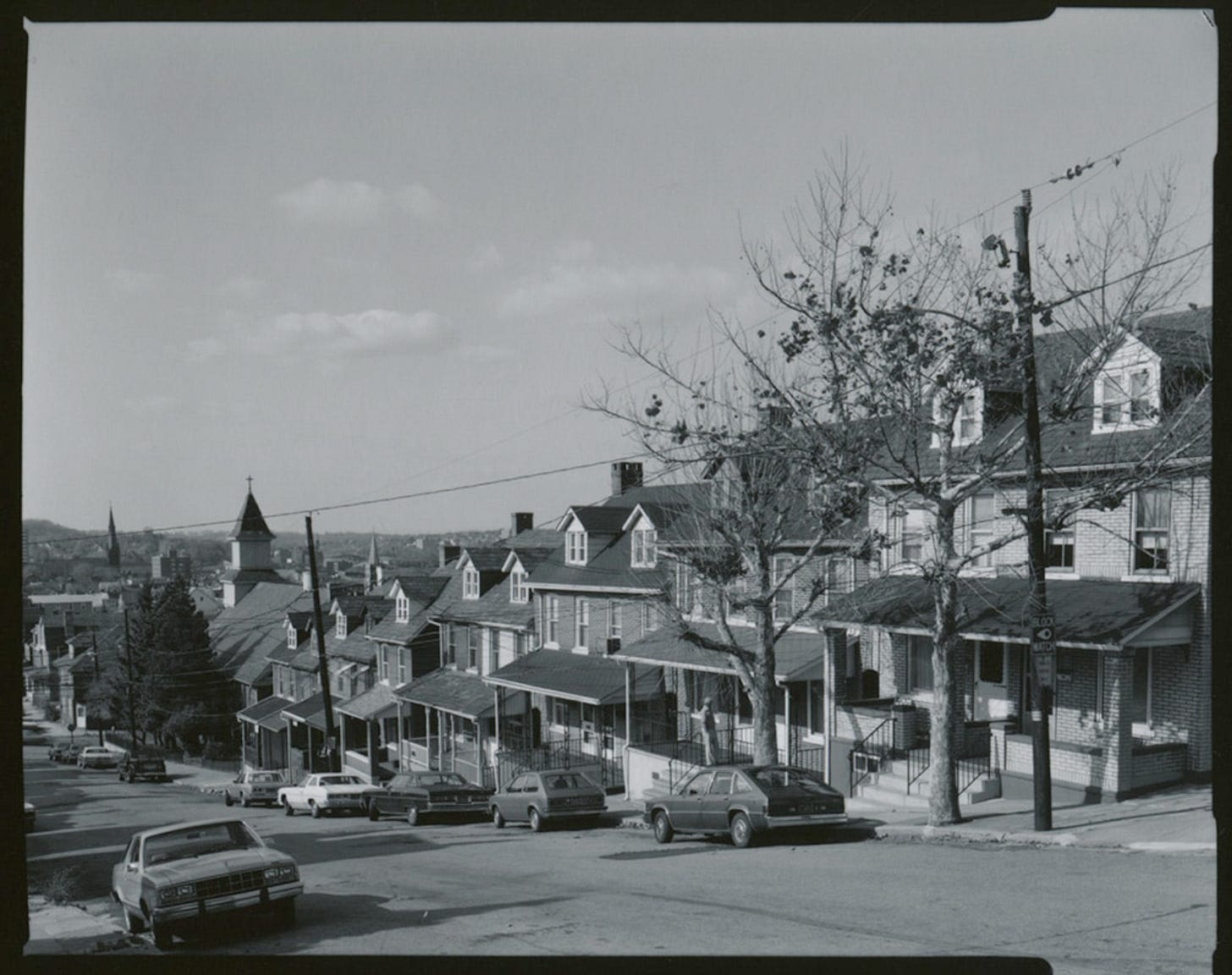

The influence of some photographers on their younger counterparts has been profound. Perhaps the best example is Walker Evans. Robert Frank, Garry Winogrand and William Eggleston have all spoken about their debt to Evans.

I think the photographers who I feel that I learned the most from, most immediately, who I feel most responsible to, are Walker Evans and Robert Frank.

— Garry Winogrand

In 2020, David Campany curated the Biennale für aktuelle Fotografie: The Lives and Loves and Images, featuring Walker Evans Revisited. Campany selected a wide range of artists who have responded to Evans in two main ways:

Firstly, there is the continuation and extension of his manner of photographing everyday life [...] Secondly, the exhibition presents a variety of projects by artists responding very directly to particular images and projects by Evans. These range from appropriation and collage, to re-imaginings and homage.

— David Campany

Including Sherrie Levine’s After Walker Evans, Justine Kurland’s Labour, Camille Fallet’s License Colour Photo Studio and Mark Ruwudel’s Evans Street #1, Campany offers us a brilliant and diverse survey of one photographer’s enduring impact on the history of the medium.

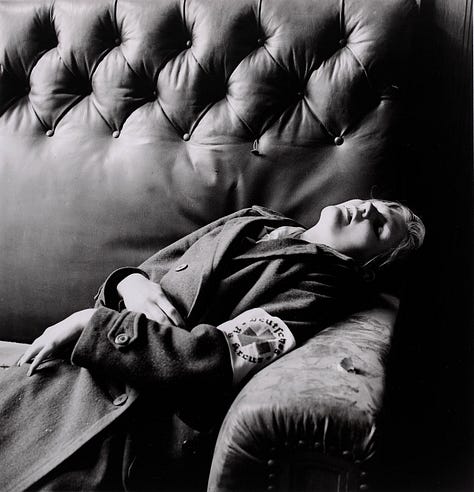

One of my favourite examples of explicit homage is Viviane Sassen’s ‘Lacrima’, a response to the photographs (and character) of Lee Miller.

Miller and I share certain experiences: we were both fashion models in our younger years and she, too, was employed as a commercial photographer in order to finance her more personal work […] I relate to Miller’s distrust of dogma and her intimation of the uncanny and the grotesque: a shadow is always present. That said, humour is never far off. What most attracts me to her pictures, though, is her free thinking and the surrealist eye she cast upon the world […] By translating some of my ideas into black and white, I’ve tried to pay homage to Miller’s work in a direct way. I like to think about how my photographs might have looked if I had lived in her time. Yet, for me, the images Miller created don’t exist solely in the past: her legacy moves through time, like a river.

— Viviane Sassen

I like Sassen’s use of the word ‘translation’ here and the notion that a photographer’s legacy is like a river, flowing through time. Despite what she says about the directness of her homage, I don’t think anyone would argue that Sassen’s pictures look like Miller’s. The nature of the homage is subtle, nuanced and metaphorical and all the more impressive for it. Sassen has absorbed the spirit of Miller’s work (and life).5

A photographer's influence can be felt in many ways - their choice of subject, their photographic philosophy, their preferred equipment, their politics, their approach to captions/titles, their preferred publishing format etc.

In an educational context, copying (even borrowing) is frowned upon. Anxieties about the increasingly pervasive use of Chat GPT by students, access to mobile phones and stringent examination arrangements are all fuelled, to some extent, by a desire to prohibit direct imitation. In the specific realm of photography education, copying is not only unavoidable (for a whole range of inter-connected reasons) but it’s also, in my view, something to be acknowledged and embraced.

Copying is how we learn.6 Copying requires lots of positive attributes - focus, inquisitiveness, intrinsic interest, care, attention to detail etc. Copying is not cheating. It’s a kind of collaboration with an imaginary accomplice.

Of course, selecting an appropriate model from which to copy is also a key attribute.

Think about the skills and patience required to copy an image by an admired photographer. There’s clearly a difference between good and bad copying. But the attempt to copy (in photography) is fundamentally educational. Done well, it involves deep research, planning, trial and error, refinement and critical reflection.

So, here are some suggested ways in which you can reframe, for yourself or others, the notion of copying in photography:

Choose a photographer/artist who you admire. Make a list of all the things you love about their work. Try to be as detailed and specific as possible.

Select 5-10 of your favourite images by this photographer. Either print them out so that you can then cut them up to make a physical or digital collage. Be imaginative. Your collage could feature important details from the photographer's pictures or, for example, you could use the negative spaces and leftovers of the images once the important details have been removed. Think about how you are both celebrating and translating your favourite photographer's work in the process of making your collage.

Using a similar (or identical) group of photographs by your favourite photographer, re-photograph them in various ways. You could photograph versions of them on a screen (phone, tablet, TV or computer). You could print them on glossy paper and photograph them with light reflections disrupting their surfaces. You could use a macro lens to make extreme close-ups for particular details. You could place two images next to one another and photograph the join between them so that you create a type of diptych in which only half of each image is visible.

Imagine you are the curator of an exhibition of your favourite photographer's work. You could create a physical model of your exhibition space, printing out and installing (at various sizes) the images. You could imagine that a single piece of paper (A2 or A1) is a gallery wall on which you could 'hang' the work. Alternatively, you could use digital software (Powerpoint or Google slides, for example) to construct a virtual room by room version of your exhibition. Think carefully about the introductory wall text (helping visitors to understand the context of the work) and any additional captions or supporting information. What will be the title of your exhibition and how will this help visitors/viewers begin to think about the way in which you have interpreted the photographer's work? Threshold Concept #7 might help you reflect on the ways in which photographs rely on context for their meaning.

Choose ONE photograph by your favourite photographer. Re-create this photograph using non-photographic materials. You could try to make a really accurate drawing of the image, model it in plasticine, construct a version made from food stuffs etc. How will you translate the photographer's use of tone/colour, shapes and forms, line and pattern etc? How might you explore the relationship between three dimensions (the subject of the original photograph) and two dimensions (the photograph) in your re-creation? Will it be flat (like the photograph) or three-dimensional (like the photograph's subject)?

Create your own sequence of photographs inspired by those of your favourite photographer. Decide what kind of homage you intend to make. For example, will your images respond to the genre of your chosen photographer's pictures, their visual language and grammar or the choices the photographer has made? Will you respond to something influential the photographer has said or written about photography and/or their practice? Will you respond to the atmosphere or mood or their pictures or the way they make you feel?

What do you admire most about your favourite photographer? Have you ever constructed your own deliberate homage to them? If so, I’d love to know more about it.

These posts will always be free but, if you enjoy reading them, you can support my analogue photography habit by contributing to the film fund. All donations of whatever size are very gratefully received.

However, the tendency for artists to club together to pioneer new forms led to some almost indistinguishable works of art. A certain type of copying is characteristic of the avant-garde.

The scare quotes are an acknowledgement that photography’s origin stories are more diverse and interesting than most histories of the medium acknowledge.

I’m aware that I’ve been using a variety of words that are not entirely synonymous - copying, borrowing, influence, imitation, translation, appropriation, re-imagining, homage etc. If you’ve read any of my previous posts (a) thank you, and (b) you’ll know I like a spectrum or scale. Maybe (craven) copying might be at one end of the line and (respectful) homage at the other. My point is that they are all on the same line.

I’m using the slightly triggering word of ‘copying’ here deliberately, precisely because it has such negative connotations in schools. I’m obviously not talking about stealing someone else’s work. But I’m not opposed to or offended by appropriation, as long as the person doing the appropriating has an understanding of the cultural meaning and context of their actions.

Excellent article. I will do this exercise with my advanced photo kids next year.

Thanks for this great article. Interesting topic.